I may have become obsessive during the recent Making the Australian Quilt exhibition at NGV Australia. (Getting nods from the visitor services staff is a clue that you’re there too often.) It was completely worth it to get to know my favourite quilts intimately.

Co-curators Katie Somerville and Annette Gero did a wonderful job, and I was fortunate to be invited to the opening.

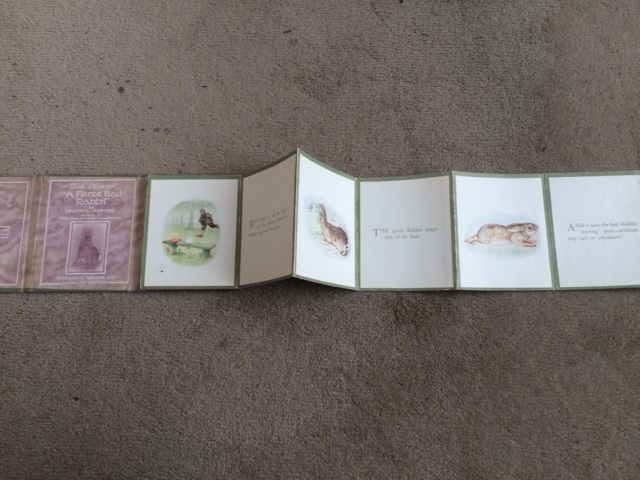

In Perth, about 2004, I went to a presentation by Dr Gero with my friend Sue, exquisite quilter and sister children’s librarian. The evening was hosted by WAQA and meeting the Child’s Quilt with Nursery Rhymes (pictured above) was the highlight of it. This splendid array of applique and embroidery looks like 42 covers in a picture book display. There are 32 nursery rhymes represented in 34 of the squares – Jack and Jill and The Queen of Hearts are depicted twice – and the eight remaining are popular stories and books.

The books were an important factor in dating the unsigned quilt – publication dates being more exact than the older nursery rhymes and stories. During that evening, I helped identify a block labelled ‘Amelia Ann’ as a book by Constance Heward, first published in 1920. (The title is actually Ameliaranne and the Green Umbrella.) Here she is.

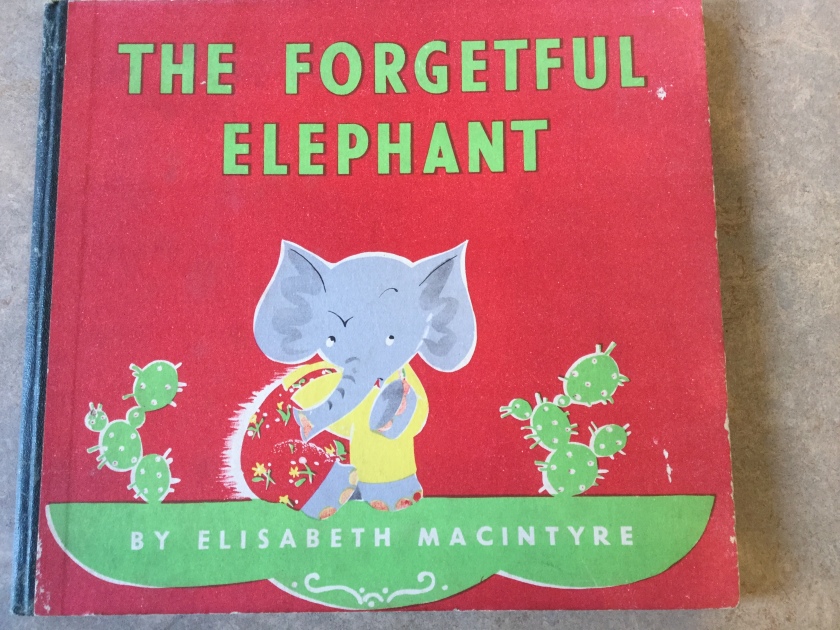

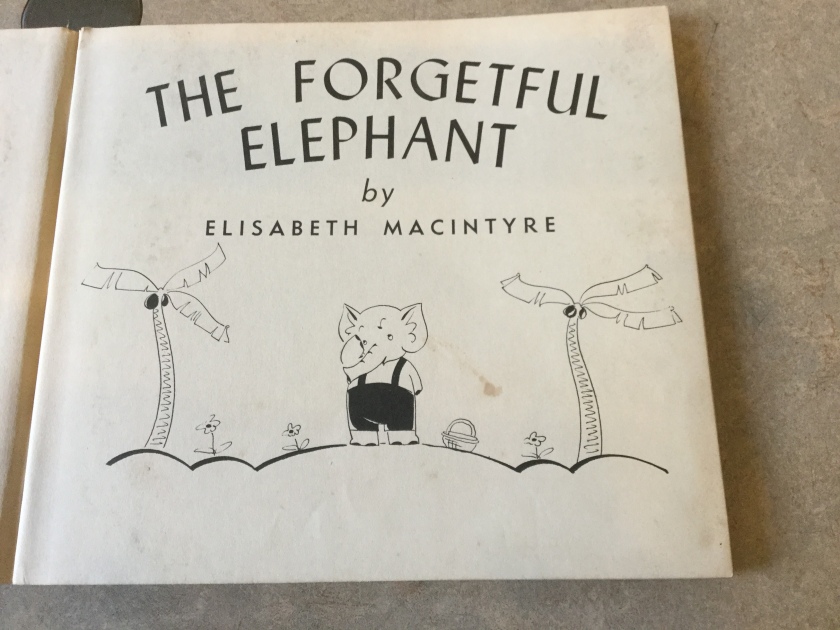

The other books were Bambi, Brer Rabbit and a mysterious gem called The Forgetful Elephant which is peeping out from behind a dressing gown in this picture.

My increasing impatience with people exclaiming ‘Look! There’s Babar!’ (have I mentioned I saw this exhibition many times?) led me on a mission to identify this story. After a false (but charming) lead, I found it at State Library Victoria.

Unfortunately the book, like the quilt, is undated, but the noble cataloguers at SLV have estimated it as 1944. It was called ‘garish and vulgar’ by a leading Australian children’s literature critic but that’s a bit harsh. Here’s the title page, which the unknown quiltmaker has used as the block design.

There was another ‘story’ quilt close to this one in the exhibition : Child’s Nursery Rhyme Quilt by Amy Amelia Earl, signed and dated 1923.

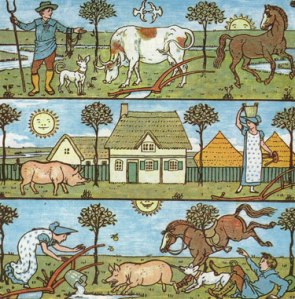

These weren’t the only quilts made for, or used by, children – Mary Jane Hannaford’s delightful Good Night quilt, made for her grandson, was another. No doubt many a bored Victorian girl amused away a Sunday looking at tiny embroidered names and figures – some designed by book illustrator Kate Greenaway – in a crazy quilt.

I began looking really closely at the nursery rhymes depicted on both of these quilts, which were companions in the exhibition, and wondering how and why particular ones were pictured. I was intrigued to see those from my childhood that my children never heard or don’t know (Dick Whittington), and to not see the most wellknown Anglo-Celtic one of their generation (Twinkle Twinkle Little Star).

I’ll be examining some of the rhymes, and how these quiltmakers represented them, in upcoming blogs. I won’t be talking about what the rhymes ‘mean’ – that’s covered by the excellent scholarship of the Opies – but I will be looking closely at how their transformation into needlework has elevated them beyond the ditty.

I did say I may have become obsessive.